I received your biopsy results. I’ve scheduled an appointment for you to come in and talk with me on Monday.”

Most of us can recall a time in our lives when bad news hits like a knock-out punch to the gut, a stunning blow that floods our senses with all the force of an imploding dam, frigid backwater coming at us in a swift noisy din and leaving us unable to breathe, flailing for the surface—wherever the surface might be. I sputtered, “I have cancer.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes, you have DCIS.”

I want to point out right away this isn’t a book for the fearless and faithful—like my friend Billi Clem, who met her DCIS breast cancer with gratitude, wonder, and a delightful sense of humor. I’m not like her, more’s the pity, but there are a lot of women who are. They face devastating loss with fortitude. I envy them, but I am not one of them. This book isn’t for them.

It’s for people like me. People who are afraid, who find faith difficult. People who seem to endure one thing after another until it becomes difficult to see light at the end of the tunnel. You see, cancer isn’t my first crisis. Nor is dysautonomia my friend Valerie’s, or macular degeneration Barbara’s. With each new trauma or disappointment, people like us stumble about in familiar darkness of heartache and want, unable to navigate our way to safety while everyone else seems to lead normal lives.

Most of us can recall a time in our lives when bad news hits like a knock-out punch to the gut, a stunning blow that floods our senses with all the force of an imploding dam, frigid backwater coming at us in a swift noisy din and leaving us unable to breathe, flailing for the surface—wherever the surface might be. I sputtered, “I have cancer.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes, you have DCIS.”

I want to point out right away this isn’t a book for the fearless and faithful—like my friend Billi Clem, who met her DCIS breast cancer with gratitude, wonder, and a delightful sense of humor. I’m not like her, more’s the pity, but there are a lot of women who are. They face devastating loss with fortitude. I envy them, but I am not one of them. This book isn’t for them.

It’s for people like me. People who are afraid, who find faith difficult. People who seem to endure one thing after another until it becomes difficult to see light at the end of the tunnel. You see, cancer isn’t my first crisis. Nor is dysautonomia my friend Valerie’s, or macular degeneration Barbara’s. With each new trauma or disappointment, people like us stumble about in familiar darkness of heartache and want, unable to navigate our way to safety while everyone else seems to lead normal lives.

Scott Peck had it right when he opened his book The Road Less Traveled with “Life is difficult.” Yet for some, life seems to be more difficult than for others. And here’s the bad news. There are no snappy answers. This is the whole point of Job in the Old Testament, is it not? He’s the most victimized man in the Bible, yet despite his anguished beseeching, his weeping and wailing and wearing of sackcloth and ashes, God did not answer his questions. His friends sure did—citing bumper sticker theology and Facebook simplicities, dishing up isolated scripture that had nothing to do with the whole. A torment unto itself, make no mistake. Until finally God did step in. Not to comfort Job or answer his questions—but to rail at his friends for their audacity and smugness. Which begs the question then, is there hope for the troubled?

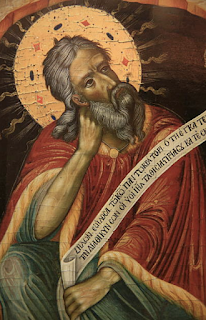

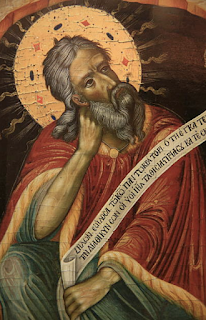

Remember Elijah? He too was from the Old Testament. He’s the chap God assigned to take on Queen Jezebel and her wicked god Baal, a god who demanded the sacrifice of babies and whose rituals involved eating feces. In a maelstrom of fire, Elijah burned down Baal’s altar; and Jezebel, in a white-hot fury, came at him with all the resources of her arsenal and army. A scary time for Elijah—much like cancer for us, and financial ruin, kids on drugs, betrayal, chronic pain, debilitating disease, divorce.

Remember Elijah? He too was from the Old Testament. He’s the chap God assigned to take on Queen Jezebel and her wicked god Baal, a god who demanded the sacrifice of babies and whose rituals involved eating feces. In a maelstrom of fire, Elijah burned down Baal’s altar; and Jezebel, in a white-hot fury, came at him with all the resources of her arsenal and army. A scary time for Elijah—much like cancer for us, and financial ruin, kids on drugs, betrayal, chronic pain, debilitating disease, divorce.

Elijah ran pell-mell for the desert where God hid him amongst the stony outcroppings of Cherith Creek. There he was, on the “Most Wanted” list, his life in peril, and all he’s got is a crummy little creek in a beastly hot desert. Oh, yes, the ravens. Foul, glossy black things they are, eating nothing all day but road kill. Yet in Elijah’s extreme deprivation and isolation, fear pummeling his gut, the ravens became God’s saving grace. They brought him bread and meat in the morning and bread and meat in the evening. Who would have thought that carrion-eating birds would be a man’s only hope of survival? It’s almost offensive. At times it feels offensive. But then, sometimes that’s what grace looks like.

This is the good news. In the tight spots, God sends us grace by way ravens. I know, I know, not exactly what we want. Filthy birds with decay in their beaks. We want “cured,” “livable wages,” “love.” We all have our list. We all want that window when the door slams shut, boxing us in with no way out. And so it’s easy to dismiss the ravens—not even see them—these creative gifts of grace in the chaos of our fear and anxiety and grief. And thus we cover ourselves in sackcloth and ashes as did Job, and we cry along with him, “Oh, that I was never born!”

My mother used to tell me I reminded her of a 1950’s baby toy, the plastic happy clowns with roly-poly bottoms that babies batted at. Easy to knock over—but, with beans in their bums, the clowns bounced right back up. Bat, bob, bounce. Up and down, bobbling around. Oh such fun! But not in real life. Such treatment for real can depress the most spirited of souls. “Life keeps taking a whack at you,” my mother would say, “but you always bounce back.” I used to ask, “But what happens if I can’t bounce anymore? It’s getting harder and harder.” I was in my fifties when I began asking, “What if I break?”

“You won’t break,” she’d say.

But I did break, and I have broken. Cancer broke me.

Living With Ravens: An Odyssey of Fear, Faith, and Grace is my story—the latest episode, at least, in a history of sometimes bitter disappointment. You see, my whole life can be viewed as a struggle between fear and faith—and grace. And so I write for people who can’t be made whole anymore by biblical talking points, bumper sticker theologies, or Facebook triteness. Because this I know, despite our pain, confusion, and grief, despite our illness and in His silence, He nonetheless sends us the ravens when life puts us again in isolation at the lonely, barren shoreline of Elijah’s Cherith.

One day in the parking lot of my son’s workplace, I was again in tears. Cancer’s complications were taking their toll and each visit to the plethora of doctors only served to deepen my despair. Like Job, I was on my knees, wailing, weeping, beating my chest, dressed in sackcloth and ashes. Like Elijah, I was back at Cherith and stuck there—isolated in the beastly heat and dribbling creek of the desert. It can be a nasty business for the beleaguered. How was I to go on? I looked up and saw love and a kind of anguish in my son’s eyes.

“All I want right now,” he said to me, “is to enjoy the day with my mother.”

There it was, a raven in the desolation; divine grace in the wilderness. Suddenly all I wanted was to spend a day with my son. We went out to Marymoore Park where we biked through the trees; we kayaked, too, along the riverbank where dragonflies zip-darted over the water’s surface.

You see, God will find a way to penetrate the evils of this world to give us hope. In my case, to whittle away at the false doctrines of health and wealth to a greater understanding of God’s infinite capacity to inspire awe. The riverbank, the dragonflies. A son who loved me. And in the end, is this not what God did for Job? Inspire awe? No answers to Job's brow-beating questions. No insight into the evils that befall. Just questions of His own. “Who set the stars?” he asked Job. “Who carved the mountains? Who put the leviathan in the sea? Who turns the earth in its seasons and sets the birds on their course?”

Remember Elijah? He too was from the Old Testament. He’s the chap God assigned to take on Queen Jezebel and her wicked god Baal, a god who demanded the sacrifice of babies and whose rituals involved eating feces. In a maelstrom of fire, Elijah burned down Baal’s altar; and Jezebel, in a white-hot fury, came at him with all the resources of her arsenal and army. A scary time for Elijah—much like cancer for us, and financial ruin, kids on drugs, betrayal, chronic pain, debilitating disease, divorce.

Remember Elijah? He too was from the Old Testament. He’s the chap God assigned to take on Queen Jezebel and her wicked god Baal, a god who demanded the sacrifice of babies and whose rituals involved eating feces. In a maelstrom of fire, Elijah burned down Baal’s altar; and Jezebel, in a white-hot fury, came at him with all the resources of her arsenal and army. A scary time for Elijah—much like cancer for us, and financial ruin, kids on drugs, betrayal, chronic pain, debilitating disease, divorce.Elijah ran pell-mell for the desert where God hid him amongst the stony outcroppings of Cherith Creek. There he was, on the “Most Wanted” list, his life in peril, and all he’s got is a crummy little creek in a beastly hot desert. Oh, yes, the ravens. Foul, glossy black things they are, eating nothing all day but road kill. Yet in Elijah’s extreme deprivation and isolation, fear pummeling his gut, the ravens became God’s saving grace. They brought him bread and meat in the morning and bread and meat in the evening. Who would have thought that carrion-eating birds would be a man’s only hope of survival? It’s almost offensive. At times it feels offensive. But then, sometimes that’s what grace looks like.

This is the good news. In the tight spots, God sends us grace by way ravens. I know, I know, not exactly what we want. Filthy birds with decay in their beaks. We want “cured,” “livable wages,” “love.” We all have our list. We all want that window when the door slams shut, boxing us in with no way out. And so it’s easy to dismiss the ravens—not even see them—these creative gifts of grace in the chaos of our fear and anxiety and grief. And thus we cover ourselves in sackcloth and ashes as did Job, and we cry along with him, “Oh, that I was never born!”

My mother used to tell me I reminded her of a 1950’s baby toy, the plastic happy clowns with roly-poly bottoms that babies batted at. Easy to knock over—but, with beans in their bums, the clowns bounced right back up. Bat, bob, bounce. Up and down, bobbling around. Oh such fun! But not in real life. Such treatment for real can depress the most spirited of souls. “Life keeps taking a whack at you,” my mother would say, “but you always bounce back.” I used to ask, “But what happens if I can’t bounce anymore? It’s getting harder and harder.” I was in my fifties when I began asking, “What if I break?”

“You won’t break,” she’d say.

But I did break, and I have broken. Cancer broke me.

Living With Ravens: An Odyssey of Fear, Faith, and Grace is my story—the latest episode, at least, in a history of sometimes bitter disappointment. You see, my whole life can be viewed as a struggle between fear and faith—and grace. And so I write for people who can’t be made whole anymore by biblical talking points, bumper sticker theologies, or Facebook triteness. Because this I know, despite our pain, confusion, and grief, despite our illness and in His silence, He nonetheless sends us the ravens when life puts us again in isolation at the lonely, barren shoreline of Elijah’s Cherith.

One day in the parking lot of my son’s workplace, I was again in tears. Cancer’s complications were taking their toll and each visit to the plethora of doctors only served to deepen my despair. Like Job, I was on my knees, wailing, weeping, beating my chest, dressed in sackcloth and ashes. Like Elijah, I was back at Cherith and stuck there—isolated in the beastly heat and dribbling creek of the desert. It can be a nasty business for the beleaguered. How was I to go on? I looked up and saw love and a kind of anguish in my son’s eyes.

“All I want right now,” he said to me, “is to enjoy the day with my mother.”

There it was, a raven in the desolation; divine grace in the wilderness. Suddenly all I wanted was to spend a day with my son. We went out to Marymoore Park where we biked through the trees; we kayaked, too, along the riverbank where dragonflies zip-darted over the water’s surface.

You see, God will find a way to penetrate the evils of this world to give us hope. In my case, to whittle away at the false doctrines of health and wealth to a greater understanding of God’s infinite capacity to inspire awe. The riverbank, the dragonflies. A son who loved me. And in the end, is this not what God did for Job? Inspire awe? No answers to Job's brow-beating questions. No insight into the evils that befall. Just questions of His own. “Who set the stars?” he asked Job. “Who carved the mountains? Who put the leviathan in the sea? Who turns the earth in its seasons and sets the birds on their course?”

Last summer and in between reconstructive surgeries, suffering chronic pain and uncomfortable disfigurement, friends and I went on an exploring mission in the Canadian Yukon for our boss, taking his posh, brand new ATVs up to Paddy’s Peak. We bounced over waist-high boulders, crisscrossed glacial creeks, wound our way up an old stream bed, climbed steeply to the alpine and a carpet of wild flowers I’d never seen before. Everyone scrambled out, headed for the glacial lake our boss intended to make as a stopping point for new tours out of Skagway, AK. Able only to scrabble the glacial rock with difficulty, I carefully followed. When I finally caught up, Bill hollered over to me, “Well? What do you think?”

I stood fully and slowly turned, taking in the 360° view. I couldn’t speak for the tears in my eyes.

“Who made this place?” God asked in my silence. “Who sheered the cliff face, dropping it 6,000’ to Lake Bennett below? Who cradled the glacier, who empties its icy lagoon? Who guides the feet of the mountain goats and who feeds the artic squirrels? Who sets the breeze to rest the birds’ wings?”

In that moment, overcome by all that God was, all that He created, all that He gives us, all I wanted to do was to bow before God, as did Job. “I did not know my soul could still sing,” I simply told Bill—and turned a corner in my soul.

My premise is that we ignore ravens at our peril. But if we can learn to recognize them, appreciate them for what and who they are, we can then know we’re not forgotten or abandoned on the stony outcrop of our pain. The same God who sends us ravens in our darkest hours is the same God who sets the universe.

He loves us.

And nothing else matters.

He loves us.

And nothing else matters.

|

| Not far from the glacier lake, looking down from Paddy's Peak onto Lake Bennett below. |

from brenda: if this would be a book you'd find helpful, please let me know.

Brenda@BrendaWilbee.com